Concert Black– Terrance McKnight personalizes the Black experience in classical music’s culture

While our collective awareness of bias and injustice towards Black people has recurrently ebbed and flowed throughout American history, Black contributions to Western classical culture are timeless and universal. We presume that the centuries-old treasure trove of Black music among the canon’s powerful, visceral accessible experiences have reached all hearts equally.

Providing evidence to the contrary of that narrative, WQXR’s Juneteenth Special broadcast in 2020, coined “the Black experience in the concert hall,” curated and hosted by Terrance McKnight, featured accounts by industry leaders and testimonials from Black musicians describing a vastly different reality.

In the wake of the killings of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd and the following nation-wide protests, many music institutions are faced with an increased urgency to not only have a necessary dialogue about social justice and inclusion, but to determine solutions that offer sustainable changes to classical music’s pedagogy and traditional performance culture.

A publisher, listening to the timely broadcast, immediately realized the importance of these essential conversations and the significant urgency to feature them beyond their current format.

As the longtime host of WQXR’s “Evenings with Terrance McKnight,” where he shares his in-depth perspectives on classical, jazz, and gospel – music he loves – on air, McKnight is currently on sabbatical until the end of May to finish the manuscript for his upcoming book, Concert Black, to be published by Abrams Books, that will continue in the vein of conversations initiated by the Juneteenth broadcast.

This article includes samples of McKnight’s on-air conversations and his personal outlook on his upcoming book.

Among some of the featured personal accounts of artists about how being Black in musical America and operating in a predominantly white concert culture transcended their lives and careers, McKnight describes his own journey and resulting advocacy.

A revised edit of this article by Ilona Oltuski, was previously published on Classical Voice North America.

Terrance McKnight is a longtime New York music-radio host and devoted musical multiculturalist.

“I always have been living between the two worlds,” says McKnight. “When I started working in radio, first in Georgia, in 1999, and DC, before I came to New York in 2008 to WNYC, that’s what I brought to my programming ideology. I tried to appeal to a multi-cultural society, by bringing everyone’s culture to the table, not putting one above the other. A couple of shows stood out to me, like Fred Child’s ‘Performance Today’ and Bill McLaughlin’s ‘St. Paul Sunday Morning’ (CBS), which had that broader perspective,” he says.

In his book, McKnight will feature a great variety of performers, ranging from Black performance veterans to new voices, like Black Lives Matter (BLM) activist and soprano Julia Bullock, a winner of the 2012 YCA competition who was also nominated for 2020 Musical America artist of the year.

Soprano Julia Bullock is among the artists featured in Terrance McKnight’s new book.

With refocused awareness following civil appeals for social justice, equity, and inclusion comes an acute sense within the music industry of its failure to create relevance around the classical music idiom for an inclusive community of diverse participants and audiences. Action must follow up the discourse that includes these questions: How can we bridge the existing disconnect with communities of color, and how can we create an inclusive culture around classical music culture’s existing presentations and practices? What needs to change in the art form’s development practices to foster and provide a welcoming culture of classical music, from its educational institutions leading into the concert hall, to make the experience matter equally for all?

“Classical musicians of African descent have existed on the margins of obscurity for centuries – in the classroom, the concert hall, the record industry, and on the radio,” says McKnight, “This underrepresentation is what brought me to work in public radio,” he says, and adds that at this moment in time, the Juneteenth presentation and resulting book have brought his mission rather full circle.

Asking the hard questions of leadership, McKnight offers important viewpoints on the diversity aspect in existing classical culture, points out what’s lacking, and aims to guide us through the challenging process of finding a way to move forward.

“Music can be on the front lines for equality and justice, just like it was for Beethoven, Rimsky-Korsakov, Chopin, and Harry Belafonte, and [it can] help us see each other more clearly,” says Terrance McKnight, when he opened his Juneteenth special forum about the Black experience in the concert hall.

“I am not alone here,” he announces, “my WQXR colleagues are with me,” he assures us, after quoting African American poet Langston Hughes, central figure of the Harlem Renaissance, lamenting the hardship of the Black experience that kindles broad understanding of activists’ calls for change.

Words that ring in the portrayal of a process that has been ignited by the ongoing BLM protests, defined by The New Yorker music critic Alex Ross as a “self-examination of American culture.” “The undertaking is complex,” Ross says, “the field must acknowledge a history of systemic racism while also honoring the individual experiences of Black composers, musicians, and listeners.”

While this is not an entirely novel observation, much effort has recently been invested to resolve the consistent overlooking of Black contributions in the classical music sector.

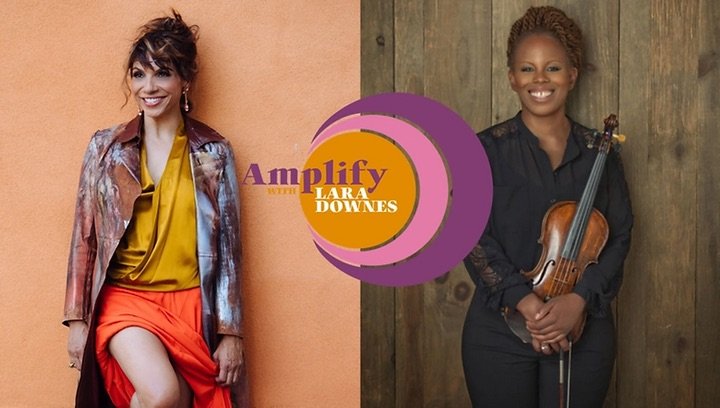

Pianist, writer, and presenter Lara Downes has produced a series of recordings by Black composers, like Florence Price and Harry T. Burleigh, and has taken the opportunity to introduce young Black and brown composers and performers on her current NPR radio show, Amplify.

(Photo: Downes, left with Regina Carter) Exploring her own identity, rooted in Jewish and Jamaican heritage, the classical pianist has crossed over time and again into the neglected chronicle of recovery of works by Black composers.

Fortified by the pandemic’s closures and re-opening anxieties of institutions, thoughts about access and elitism in the classical music field have also significantly permeated audience development efforts. One to mention would be Lincoln Center’s planned Restart Stages, which will invite performers from all of NYC’s diverse arts communities in the hope that their collective audiences may follow.

Still, many of us are hearing about the fascinating protagonists of a neglected segment of American music history for the first time. Black figures in the orchestra, for example, like Margaret Bonds, the first African American to perform with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, a composer and arranger known for her collaborations with poet Langston Hughes, or William Grant Still, the first African American to have an opera produced by the New York City Opera, and Eubie Blake, who co-authored one of the first Broadway musicals written and directed by African Americans.

Former League of American Orchestras President and CEO Jesse Rosen ( Photo: WQRX)

McKnight intersperses observations from industry leaders, like music critic and Juilliard Professor Greg Sandow, and Jesse Rosen, who was at the time of the show the President and CEO of the League of American Orchestras, with personal accounts by Black performers, composers, and conductors, like soprano Martina Arroyo, founder of the Martina Arroyo Foundation, and virtuoso trumpeter Wynton Marsalis, Artistic Director of Jazz at Lincoln Center.

Silken-voiced, McKnight intimately swaps anecdotes from his youth with those of some of his guests on air. His own experiences carry mixed messages, telling some stories about being overlooked, made to feel like an outsider, while others talk about being equally nurtured and encouragingly inspired.

“In grad school, I was accompanying in our studio class when a few months into the semester, the professor stood next to me in the elevator, saying: ‘How is the basketball team?’ … ‘I did not even know we had a basketball team,’ I replied: ‘I am in your studio class playing the piano.’ But to counter this, I had a wonderful, inspiring piano teacher, Mark Buser, and at Georgia State, Kerry Louis, who talked about the ownership of emotions. ‘Music is colorless,’ he said, ‘and does not belong to any one group. If you understand what love and pain feels like, on a human level – how Rachmaninov felt it – you can take ownership of this music and make it yours.’ ”

It is experiences like these that continue to motivate McKnight to advocate for the artists and the art form.

Addressing Jesse Rosen, who in September of 2020 left his post as President and CEO of the League of American Orchestras, McKnight says: “I know your organization has had its share of conversations about the racial makeup in the concert hall today,” opening the forum for Rosen’s account. Rosen responded, “Indeed, we had done two major studies, a couple of years back, one more quantitative and one more qualitative, showing artistic and social development and looking into the experience. Until now, sadly, there was hardly any movement at all. On stage, there are only about 1.8 percent Black musicians. Having that data available is turning some lights on, finally. The qualitative study gave some critical information with some equally unsatisfying findings,” says Rosen, further describing how Black musicians in orchestral fellowships largely feel “tolerated” rather than supported by their respective organizational cultures.

“In 2020, more and more organizations started to come up with a shift in mission statement of equity, diversity, and inclusion, and we are finally addressing a perpetuation of a system, to address their own internal structures of racism,” says Rosen. Currently 180 Black musicians receive mentorship and audition training through programs in collaboration with the Sphinx Organization and the Mellon Foundation, which Rosen believes are essential steppingstones in the journey toward the removal of existing barriers.

With 80 orchestras on board, these initiatives carry a hopeful message of change, especially with Rosen’s vision of a changing artistic mission altogether.

“So how would the ideal orchestra look now, what would be different?” asks McKnight.

“If we were to contract an ideal orchestra right now, our guiding principles ought to start with the question of who is in the orchestra, what would they sound and look like. I would also like the work to be grounded in an expansive artistic vision, not bound by the structures we build for concert construction, constraining orchestral musicians to rehearsals and performances; we got mechanized in the process. There should be a variety of repertoire and a wider engagement with the audience. Musicians are people, who are guiding the artistic evolution of the ensemble; there should be ownership. There are ways to break down some of these barriers to strengthen and revitalize the artistic work of the orchestra,” confirms Rosen. And, as Alex Ross points out: “with a vibrant roster of younger talents moving to the fore—Tyshawn Sorey, Jessie Montgomery, Nathalie Joachim, Courtney Bryan, Tomeka Reid, and Matana Roberts, among others—the perennial solitude of the Black composer seems less marked than before.”

The problem, however, is not only with representation and repertoire. Issues of equity and diversity reach into the echelons of arts organizations’ leadership and are anchored in the structures of its breeding ground: the unequal access to music education within the American public school system.

Principal Oboist at the Nashville Symphony shares his own experiences and has suggestions on what steps should be implemented for that to change.

Titus Underwood, principal oboist of the Nashville Symphony (photo: WQXR)

“I am the first principal of color within 80 major symphonies to have tenure,” he says. “Musicians create unions, they negotiate contracts. We make sure, when negotiating these contracts, there is a corrective action that considers the factors of privileged communities. We will have Black administrators and will hire Black musicians., it should not be necessary to receive a financial incentive to hire Black musicians. It should just be done, to foster that power to be there and partake, having the same right as any other musicians. Jesse [Rosen] was talking about the experience of being unsupported. I regularly perform at the Gateway festival, which is an all-Black orchestra, with players coming together for a week or so. Playing with that orchestra feels like a family reunion. … We take great pride of being part of this canon. But it is hard, sometimes, to feel you have reached the pinnacle of what classical music has to offer, when you don’t feel the communal connection. I would like to bring the team, that would affect true cultural change. Tenured contracts make that happen, and it’s time to not only have the conversation but for action. We already know what to do.”

A true transformation would indeed require a systemic change of all processes in the classical circuit, including how admissions to conservatories are regulated, how orchestras and management scout for talent, the role of executives in the realm of institutions, and how ticket sales are directed to respective audiences.

Many times, we hear of the importance of having Black role models for the young generation to be inspired – not only by the art form, but by the fact that that classical music is played by someone they can easily identify with.

Conductor Leslie Dunner

Conductor Leslie Dunner, (photo: WQXR) who started his music training as a clarinetist only thanks to the bussing initiative of the 1960s that transferred him to a different neighborhood – which was predominantly Jewish and white – where access to music education was available. “Now I am working with High School kids,” he says. “We as professional [performers] have to instill a firm belief that we believe in what we are doing. We are role models for youth. When I was studying conducting at Eastman, some of the other students did not take me seriously. My professor supported me by [telling those students]: ‘He will be the one hiring you for your next gig…’ that was empowering,” he shares.

Liz Player, (photo: WQXR) who reports that for a long time, she was the only Black musician in some of the orchestras she performed with as a clarinetist, remembers how welcomed she felt at the New York City Housing Orchestra, filled with Black musicians: “It became all about the music, not about fitting in,” she says. Inspired by this experience, she founded Harlem Chamber Players and currently acts as its Executive and Artistic Director.

As an artistic advisor to the ensemble, McKnight is involved with some of its presentations, among his curated concerts at the Billie Holiday Theatre and at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. He also regularly curates a variety of performances and concert talks at Merkin Concert Hall, and the Museum of Modern Art, and he serves on the board of the Bagby Foundation and MacDowell. McKnight’s insights and advice on cultivation of diverse perspectives are frequently sought out by major cultural organizations.

“From time to time, I do go to a school [to do] outreach,” says McKnight. “I try to speak from a place of meeting them where they are – I don’t make it about culture but having fun with sound. I try to speak about music as a way to engage and to connect with people, not to aspire to some higher culture,” he explains. “We have to be realistic about racism, it’s been a social club for so long. And there are many who sit on boards, who want to keep it that way. Images of what it was like to be Black are still in the minds of people: not only white ones, but Black ones, like the so-called ‘Black face minstrel shows’ on TV still in the 1990s: full of bias, depicting stereotypes. I still do feel the expectations that were there, growing up in a church, with my father at the table, discussing what could be done to make people feel more welcomed. I always brought my musical language to it; it required to look around for who stood out, making everyone feel welcomed, being able to gauge the emotion in the congregation around me. I brought this to my programming for my radio shows,” he says.

( photo: Chester Higgins, NYTimes, Terrance McKnight at home)

Making use of the pandemic-induced solitude, next to working on his manuscript, McKnight has devoted himself creatively, to arrange Beethoven’s piano music to poetry readings of works by Langston Hughes, describing this artistic realm as “a place I always lives in.”

“Bringing these two different giants together helps break down barriers,” he affirms. Crossing time from the 19th to the 21st centuries, through the artistic process, is possible. Concerning social realities, he says:

“It is an important time to devote to what works – so far what we have tried has not been working – let’s try something more internal…perhaps. Naturally, not everyone has a microphone…but during the last pandemic, just about 100 years ago, Black art flourished. I think in a time of so much crisis, Black artists wanted to bring forward their strongest fearless voice, in the vein of speaking one’s truth – it has a strong potential to change us all a little bit.”

About Terrance McKnight: As a teenager, McKnight played trumpet in the school orchestra and played piano for various congregations around Cleveland. At Morehouse College and Georgia State University, he performed with the college Glee Club and New Music Ensemble respectively and subsequently joined the music faculty at Morehouse. While in Georgia, he brought his love of music and performing to the field of broadcasting. In 2010, McKnight was awarded an ASCAP Deems Taylor Radio Broadcast Award, and for the past 13 years, he has hosted his evening shows on WQXR.